Part 3: Universities are platforms

This is Part 3 of an eight-part essay, ‘So, You Run a University?’. This essay is authored by Darcy W.E. Allen, Chris Berg, Sinclair Davidson, Leon Gettler, Ethan Kane, Aaron M. Lane and Jason Potts. The previous part is here.

Picture the dean (president, provost) as a seal with a giant ball labelled SPECIAL INTERESTS precariously balanced on their nose. — Henry Rosovsky (1990: 249)

Pointing out that universities are platforms seems straightforward enough. But universities aren’t simple platforms with one, two or even three sides. They don’t just match teachers with students for one-off lectures. Rather, universities facilitate trades between teachers, undergraduates, research students, researchers, industry, alumni and of course governments. Each of these groups benefit from the others joining and using the platform, but they all want different things at different times. The breadth of trades that university platforms support is remarkable—over the past century they have grown into some of the most complex platforms in the economy. And so we must dive deeper into the notion that universities are platforms with many sides. How many sides are there? What do they want to trade? How are they managed?

The growing university

University education has grown at an incredible speed. The twentieth century saw universities balloon by as much as a factor of 200.[1] The percentage of the relevant age cohort attending university grew from less than one percent to over 20 percent worldwide. Today in G20 countries over 40 percent of the relevant age cohort attends university. Why have we seen this growth?

The global population boom (from two to six billion people) together with rising industrial prosperity meant that children of the growing middle classes demanded education. Universities obliged. They added more departments, particularly business schools. Harvard Business School, which pioneered the MBA, was only founded in 1908. All sorts of vocational training was swallowed into the remit of universities, especially after the 1960s. Teaching, nursing, social work, accounting and dentistry came to require university education. Waves of public sector reform meant many former Trade Colleges, Vocational Education Institutes, Arts Schools and Polytechnics were upgraded to university degree-granting status.

Governments became increasingly willing to fund university education to solve societal, economic and military problems.

Universities could ameliorate labour market disruption and demographic bulges. For the vast numbers of returning WWII veterans in the US, the ‘G.I. Bill’ created free university places.[2] During the post-war boom, governments in many countries successfully campaigned to make higher education free. University fees were abolished in 1962 in Britain and in 1974 in Australia. Those fees did not return until almost the end of the century.[3]

Universities became a key part of a long run strategic national investment in ‘human capital’.[4] They created smart and prosperous economies. Economists were making it clear to governments that while education had private benefits, there were also significant positive externalities or spillovers from education investments. Private markets would invest too little in higher education. And so governments were advised to step in and subsidize supply, pushing us towards the optimum societal amount of education.

Universities became a tool for industry policy and technological development (now known as innovation policy). They created innovative economies. Eisenhower's famous parting shot about the military-industrial complex was actually originally titled the academic-military-industrial complex.[5] The US’s chief scientist, the MIT engineering professor Vannevar Bush, argued for the strategic importance of large scale support of research universities to drive industrial technological development. Universities have been part of industry policy since the great Prussian political economist Friedrich List argued the strategic importance of Germany’s research universities in driving industrial catch-up with Great Britain in the late nineteenth century.[6] These same arguments echoed through the national public funding of new and ambitious universities in the industrial rise of East Asia, and then China.

For these reasons and more, throughout the second half of the twentieth century, public funding of university growth was good retail politics. It worked for burgeoning middle class voters, who wanted better things for their children. It worked for national development, as large scale public investment in a key economic resource. It worked for business, subsidising and selecting skilled labour supply. It worked for industry, delivering early stage R&D. And it worked for society, as universities became increasing centres of cultural progressivism and youth political activism.

Before the twentieth century, universities were still platforms, but they had far fewer sides. Over time the various roles that universities played accumulated. Universities did not just grow. They were doing more things for more stakeholders, and this increasing stack of deals across the economy and society needed to be brokered. Universities didn’t just need to educate, they needed to innovate, research, provide job-ready graduates, create vibrant cultural spaces. Universities became a tangle of stakeholder complexity. And all of that complexity needed to be managed.

There is also a mistaken tendency to see university growth, particularly into more market-facing endeavours, as making universities seem more like big businesses, or ‘degree factories’. This is a beguiling metaphor. But it is wrong. A business, even a vastly complex industrial factory, has ultimately a relatively simple management imperative: make profit, according to accountants, and within the rules, according to law and regulators.

Politicians sometimes try to channel this market sophistication. For instance, in 2018, Australia’s then education minister Simon Birmingham urged universities to “place student outcomes at the forefront of their considerations to meet the needs of our economy, employers and ultimately boost the employment prospects of graduates.”[7] Warming to his theme he reckoned that “By further incentivising performance in areas such as employer and student satisfaction, completion and retention we should see better outcomes for graduates and better value for taxpayers.” If it was only that simple.

From shareholders to stakeholders

It is a common trope of criticism to refer to the modern university as a ‘learning factory’. Behind this secular admonishment of industrial corporate pretensions is a romantic belief that the university needs to hold to its avowed charter to faithfully reproduce what Deidre McCloskey calls ‘the clerisy’ and minister to the souls of a priestly knowledge elite.[8] The university must be untainted by industrial forms and corporate agenda. The problem with this demarcation of the sacred and the profane, and the allegation that the university has become heretical, is that education production is nothing like factory production.

The typical factory business model is based on assembly and production for profit. The job of the factory boss is to order people around and reallocate resources. Sometimes the boss might add or remove a product line, buy some new machines, or rebalance their workforce. Ultimately their job is to put into practice some strategic vision that accords with fiduciary duty to shareholders. And what shareholders tend to want is profit.

Universities don’t have shareholders, they have stakeholders—and those stakeholders each want different things. The job of a university boss is not to maximize shareholder value. Their job is to manage and coordinate stakeholders. That management involves creating patterns of side-payments that facilitates and grows the multi-sided market. The university boss doesn’t simply deploy resources to a set of objectives. They must continually negotiate complex and often opaque side deals between stakeholders. The job of the university boss is far closer to the dark political arts of negotiating with competing, and even warring, interest groups.

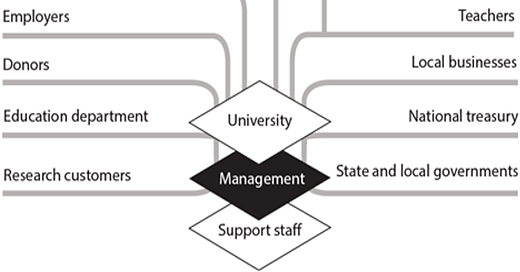

Universities are 15-sided markets

A university platform generates many benefits for many people. Teachers, students, alumni, government and industry make trades for education, research, graduates and more abstract outcomes like a growing economy or a vibrant community. Each of these stakeholder groups—sides—benefit from the others being there. To expand the size of the university platform, university presidents and leaders need an intimate understanding of these sides. Leaders need to know what those sides want, who they must trade with, and how they change over time. This knowledge is a big ask given that there are at least 15 different sides.

Students enter the university platform as unbadged and uneducated and leave with (some) extra human capital and a credential.[9] They benefit by being matched with educated and knowledgeable faculty, and faculty benefit from access to top students. Students pay fees for access to the lectures and tutorials delivered by faculty. Universities often differentiate themselves on this basic student-faculty relationship. They wheel out superstar academics and notoriously rigorous styles of teaching to attract students to their platform.

These trades are not a find-your-own-adventure. There are strict rules, such as the sequences of how those trades must take place. Degrees are arranged into courses. Those courses have learning outcomes, prescribed learning materials, assessments and exams. The structure of these rules are often made closely with regulators. Finally, if all of those trades have taken place—and if the knowledge has been successfully transferred from the faculty to the students—then those students get their credential. It is the university platform that has facilitated this basic education trade. Those trades may have been prohibitively costly without university services: imagine the cost for a student to individually search, negotiate and enforce matches with each individual teacher.

But students don’t just want education—students want jobs. And so they use the university platform to match with industry, alumni and governments. Some students want access to private companies and government graduate jobs (reciprocally, industry wants access to those students too). Research students want jobs too, but those jobs come through connections to faculty and hiring committees. All of these student-industry trades are facilitated within the university through career advisors, graduate fairs, guest lectures, internship programs, ‘applied’ or ‘work integrated’ learning, and professional development.

The distribution of student fees gives clear insights into how some university cross-subsidies work. It is clear that what students pay does not directly transfer to the wages of the faculty that educate them or the industry and career advisors that get them jobs. For many domestic students this is because the underlying profitability of teaching different courses is obscured. High-margin education in the humanities cross-subsidies low-margin education in the hard sciences.

The typical foreign student (even out-of-state student) is charged higher fees than domestic students. Higher fees for the same product. Some of this discrepancy can be explained by government regulations, where governments often encourage domestic student places. What we do know is that foreign student fees cross-subsidise other activities on the university platform, particularly research. In turn, those research activities increase university rankings and reputation, attracting more highly mobile foreign students. Aside from cross-subsidizing research, foriegn students also impart other benefits onto the university platform, acting as a bridge into new pools of potential future students and international research income.

Research students (postgraduates) play many roles to many sides of the university platform. To receive research training, these students both pay and get paid. Graduate students require faculty time and resources to learn how to produce high-quality research and how to play the academic game. But they also add value to the platform. They can publish high quality research under the university brand, improving university rankings, drawing in more students, faculty and industry to increase the size of the platform.

Many others also benefit from the activities of graduate students. They are potential tutors or assistants to teaching or research faculty, contributing to the student-faculty trade described above. Governments value them as a key component of the future workforce and as a contributor to the national innovation system. And industry uses them for industry-relevant research outputs, often paying for scholarships and laboratories. So payments flow to and from them among different stakeholders on the platform, often leaving graduates with a zero-price education.

University faculty are often so dazed, confused and bitter about precisely what their job is because they service many sides of the university platform beyond what most people think they do: teaching. They must be both teachers and researchers. As teachers they must ultimately satisfy student demands for quality education. But they must also satisfy governments (skills needed in the future economy), parents (concerned with their children getting jobs) and industry (who demand specific skills). As researchers, faculty are concerned with their own career prospects because most of the promotional game of universities is based on publication. But their research also contributes to the reputation of the university (and its ability to prove that to government funding agencies, and pull in more students), to the needs of industry and society by advancing knowledge, to the prestige of donors and alumni, and—if the miracle does happen—then also to their own teaching.

To successfully navigate and succeed in the university platform, faculty need a suite of skills that map to many different sides. They must get high teaching scores (for students), win research grants and get quality publications (for reputation), impact policy (for governments), lure parents and donors, and impart useful skills (for industry). Of course none of these skills is taught in graduate training.

Industry plays dual roles in the university platform: employers and research customers. As employers industry are interested in the quality and type of university graduates. The university platform matches students to jobs and industry to candidates. Employers demand graduates with specific skill sets complementary to their business. And so industry designs course content and checks it aligns with their needs. They deliver guest lectures to students to tell them the skills that they need. They sponsor hackathons and student events to get preferential access to a competitive pool of talent. These activities are of course all wanted by students, parents, high schools and governments alike.

Industry aren’t just employers, they are research customers. They access the university platform for frontier research that makes their business more productive and competitive. Here they aren’t concerned about the skills of graduates—they want to direct research priorities. And so they fund contract research with leading faculty. They also want people to know they are research customers, and so they sponsor research centers and do signing ceremonies.

Professional associations also trade on the university platform. These bodies can be research customers, often seeking knowledge about the trajectory and future of their industry. They can be quasi-regulators, responsible for different forms of occupational licensing (e.g. accountants, architects, medical practitioners). That licensing can be directly linked to education content and the demands of the industry. Entangled with these roles are demands for executive education and professional development competencies and skills in the profession, often responding to changes in the industry or meeting professional development requirements.

Governments now use university platforms for a remarkable array of goals. Each department and level of government want vastly different things from the students, teachers, and researchers that they find on university platforms.

At the federal government level there is a deep desire for a productive economy. They want universities to produce a pool of productive innovative high-income tax paying graduates. Federal governments want the skills of graduates to match with employers and with the future direction of the economy. And so they tweak funding models and incentives to direct the paths that students take. They want to see evidence of research ‘impact’, ‘translation’ and ‘commercialisation’. And so they make government funding contingent on this evidence.

At the state and local level governments care about, and benefit from, vibrant multicultural university communities. They want students and faculty to invest in local housing and local businesses. State and local governments want effective connections between local schools and university placements. And so state and local governments help build university infrastructure and support necessary zoning changes.

The benefits of a large effective university platforms spillover into local businesses and suppliers. Students and staff use local restaurants and bars, attend the doctor and other professional services, and encourage construction investment. That’s while you’ll find local businesses creating special deals for students and staff, running trivia nights, and sponsoring university activities.

Another group who has a strong and irreversible stake in the prestige of the university platform are alumni. They matter because the value of their degree is tied to the quality of the current student cohort and the university's research output. Alumni therefore want to ensure that future students are successful. Alumni don’t just take from the university platform, they also provide lasting industry links—they hire other alum. Alumni generate revenue by returning for further study, recommending the university to their children, or bringing in resources from their own companies or network. And of course many alumni become donors. They fund high quality socially valuable research projects, name chairs, and want to tap the networks and social circles of other donors.

Then there are the sides that closely influence and direct the ques to enter the university platform: high schools and parents. High schools and their career advisors want their students well placed and universities want the best students. High school-university partnerships shape student choices, creating institutional pathways. And these pathways connect high schools to the research prestige of the university and its alumni networks.

Many choices of prospective students about where to study are of course made by parents. Parents closely influence, and often directly fund, students. They are a key stakeholder in the key revenue source for the university. They escort their children to open day, counsel them on where and what they should study, and ultimately act as a bridge between high school and higher education. Given the stake in their children’s education, parents benefit from a legacy admissions process. Additionally, industry connections and the prestige and reputation effects that quality research brings.

***

New technologies have expanded the scope and size of digital platforms across the economy. Universities must also be understood as part of this digital corporate set. Universities are ‘matchmakers’, which was the title of a 2016 book on the economics of platforms by economists David Evans (from the University of London) and Richard Schmalensee (from MIT).[10] As they explain, these matchmakers operate under a completely different set of economic rules.

Traditional manufacturing businesses—factories—would buy raw materials, manufacture stuff and sell that stuff to customers. But being a multi-sided platform is different to being a factory. The raw material for a platform are the different groups of customers that they bring together, not anything they buy. Part of the stuff they sell to each group is access to members of other groups. All of them operate physical or virtual places where the different groups trade.

In the same way, university platforms match 15 different stakeholder sides to trade. Scholar-student. Researcher-government. Employer-student. Government-taxpayer. These patterns are even more complicated than they first seem. Take what for instance looks like a simple match: scholar-student. Undergraduates benefit from the presence of high quality graduate students, as they make fine tutors, as do research scholars, because they make fine assistants. But graduate students benefit from the presence of high quality undergraduates, because they create demand for their services, and from the presence of high quality research scholars, because they can be good supervisors.

Benefits go in all directions, so the question of who pays who is not at all obvious. Now multiply that out by all the other stakeholders who benefit from different parts of the university in different ways. Each one of them is using the university platform in exchange for their interests with many different bargaining points and price points. Hopefully the university becomes more valuable to each group as higher quality and more other groups are on the same platform. Good platforms will leverage these ‘indirect network effects’ because they give platforms a competitive advantage. But then we run into the ‘chicken and egg’ problem—who comes onto the platform first?

Bootstrapping and running any platform is hard, even with only two sides. Universities have 15 sides. Each of these deals needs to be brokered and negotiated. How do you manage a market? How do you manage a 15-sided market? From this perspective we can see why good university presidents are paid a six or seven figure salary. And it also begins to explain what looks like a ballooning university administration and bureaucracy.

In defense of administration: A platform perspective

Our platform model of a university means we must re-examine some basic questions of strategic management. What are the ‘core competencies’ of the university that create its ‘competitive advantage’? We have an uncomfortable answer: administration.

Let’s first look at the factory model. Say the main outputs of the university factory are teaching and research. The inputs into that process are teachers and researchers. These inputs are what is strategically valued by the university. It is the scholars that are important and must be guarded and nourished. University administration is there just to make sure the factory and the process runs smoothly.

Our platform model of a university offers a vastly different strategic perspective. The core competencies that give a university its competitive advantage—which is to say the valuable essential resources that need to be inside the university—can also be its administrative platform. The administrative platform is what manages its complex set of stakeholders and facilitates the functioning of the multi-sided market. In Part 5 below we’re going to give this concept a name—a ‘Hart asset’, named after Nobel Prize winning economist Oliver Hart—but for now let us unpack this problem somewhat.

Our argument makes an intriguing proposal: the most strategically valuable part of a modern university platform is its administrative capability and competencies. Not its front-line scholarly staff or academic workforce, but the administrative capability that facilitates the 15-sided market.

The administrative competencies of the university don’t fit well with the romantic and industrial visions of the university outlined earlier. Administration is always on the sideline. And so we don’t think about administrators very often. So, what exactly do we mean by this administrative infrastructure?

The organizational structure of a modern university is headed by a council or executive board and the university President or Vice-Chancellor. The board of trustees in effect represents the ‘owners’ of the university and the VC is the hired manager, or CEO. Apart from the fact that the board is a board of trustees not shareholders, at this point the university looks like any large public corporation.

Beneath the executive office are a suite of senior administrators, each of which has responsibility for a different function of the university. These will include administrative areas such as Enrollments, Finance, Teaching, Research, International, Commercialization and Ventures, Foundations and Alumni, Property and Services, Athletics, Diversity and Inclusion, Public Safety, Libraries, Community Engagement, Industry Engagement, Government Liaison. The list goes on. Each of these areas have an organizational hierarchy and budget. We will also find CTOs, CFOs, CIOs scattered throughout.

The university itself will be organized into scholarly territories called called Colleges or Schools. Each of them will report to the VC and a Provost. The administrative leaders of these entities are Deans or Heads. Nomenclatures proliferate. There are Vice-, Associate-, Deputies- and Assistant for all of these roles, and often several. All administrative staff have support staff. And that’s without even getting to the Professoriate and Fellows who do the teaching and research.

The depth and breadth of the administrative machine in the modern university is staggering. But why? A well-run factory will have lean administration. A well-run university will have enormous administrations.

The core business of a university is quantifying qualitative factors. It achieves this task through a process—a university is a flow. Universities first take in individual, idiosyncratic, opaque, unique, qualitatively distinct factors (i.e. student candidates, but also academic hires). Then it assesses refinement (teaching) with near continual monitoring and grading (assessment and exams). The process produces certification (credentials). If effective, that certification will be trusted and leveraged by external parties such as employers, family and government. The administrative process is how a university does this. The process creates value through disambiguation of uncertainty.

The administration also maintains the multi-stakeholder bargaining and contracting of a 15-sided market. A university is a nexus of contracts. Production is made with effective coordination and matching. A university is a distributed production process where value is created through quality trades: students with teachers, students with others students, researchers with colleagues, students with employers, scholars with granting agencies, and so on, through the many sided interactions we outlined above. An efficient and effective university is not the same as an efficient and productive factory from an administrative perspective. Its administration does the bargaining and deal-making and brokering or the trade-offs between the stakeholders. It balances different sides of the market to create the best possible environment for high quality, and therefore high value, interactions to take place.

Universities look like they have bloated bureaucratic structures. But that is a mistake that flows from the notion that universities are factories. An efficient university needs a sufficient administrative infrastructure to deal with the process and the nexus of contracts that constitute the university platform.

University administrations have expanded because universities have grown in scope and focus. Now of course universities are simply larger than they were two decades ago, and two decades ago they were larger than they were two decades before. But because universities are matchmakers they haven’t grown in a linear way. The number of possible trades and deals that need to be brokered make universities significantly more complex than they were decades ago. To be sure, there is waste in universities—we are not defending all administration. And of course universities have been recruiting new species of professional administrators and managers to ensure cost-effectiveness. But the size of the administration must always be understood in the context of the university as a platform—to deal with the process and the contracts of a multi-sided market.

Administrators and academics are like the ‘suits’ and ‘creatives’ in Hollywood. There is a lot of suspicion from academics about administrators and their vastly bloated bureaucracies. A new type of non-academic professional has emerged in the functional areas of finance, human resources and quality assurance. Grahame Lock, a philosopher at Oxford University, calls this ‘hyper-bureaucracy’.[11] Many administrators have an increased focus on ‘transparency’ and ‘accountability’. From this perspective non-academic professionals (the ‘suits’), suck up too much of the academics (the ‘creatives’) time rather than provide support to do their best work.

University administration has grown and continues to grow because of the complexity of universities. The more units there are, the more relationships there will be. We see horizontal distribution of different special functions with different departments and centres, as well as many administrative units, vertical distribution with central administration, faculties, departments and sections within departments and geographic spread with different units in different places within a particular city. External expectations and demands, formalization of education, and the internationalisation of research. These all need to be administered.

But more administrators with more power are not evidence of some kind of bureaucratic capture. The diagnosis is not necessarily rent seeking by the administrator and executive class, seeking to sap resources away from academic life. That argument might well hold up in an industrial corporation, where the mechanism to deal with that is a board replacement of the CEO, or a hostile merger. But the argument we emphasise here—an argument made by Ethan Kane in his PhD work cited above—is that evidence of administrative growth may actually instead be a sign of university effectiveness and productivity.

As the cost of student degrees has continued to rise and as student debt amasses, many customers (students and their parents) and faculty (who fret about their teaching workloads, service requirements, research allowances and other perquisites) look at the growth of administrative operations and budget and just see what looks like makework and rent-seeking. But if when we misdiagnose the university as a credential or research factory we also misdiagnose the administrative apparatus. From one perspective, administrators are fat that needs to be trimmed. They take away from the efficiency of the factory. But from another, because many university administrators work in or adjacent to income generation functions, it is easy to account for these costs as being covered business expenses.

While the growth of university administration has been widely reported at least since the 1970s, our model of universities as platforms predicts and explains that growth.[12] Unlike factories, the university is a complex contracting structure with many different interacting stakeholders that need to be administered. Now we must consider the university platform and its administrative assets in the trying times of technological shocks and a global pandemic.

Part 3 takeaways

Universities are platforms for matchmaking. Their core function is to provide a marketplace within which different stakeholder groups trade: scholars and government with students, employers with graduates, researchers with industry.

The modern university platform has at least 15 distinct sides trading on it: students (undergraduate, international, research), facultury (researchers, teachers), industry (employers, research customers), professional associations, government (federal, state, local), alumni, donors, high schools, parents and local businesses.

But all of these need to be navigated, managed and brokered. A multi-sided market needs to be managed and brokered (oftentimes without the various stakeholders knowing) to expand the size of the market.

This is the task of the university president, who must have an intimate knowledge of the stakeholder groups, and the supposedly bloated university administration, who manage the intricate deals and cross-subsidies to keep the market functioning.

While a well-run factory will have lean administration, a well-run university will have an enormous administration. The core competency of a university is not its faculty, but the administration and management that makes the university platform function.

References

[1] Schofer, E. and J. Mayer. 2005. ‘The worldwide expansion of higher education in the 20th century’ American Sociological Review 70(6): 890-920.

[2] See Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 (USA).

[3] See Education Act 1962 (UK); States Grants (Universities) Act 1973 and States Grants (Advanced Education) Act 1973 (Australia).

[4] Schultz TW 1960 Capital Formation by Education, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 68, No. 6, pp. 571-583; Becker GS. 1964. Human capital : a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education, Columbia University Press.

[5] Giroux, H. 2007. The University in Chains: Confronting the Military-Industrial-Academic Complex. Paradigm Publishers.

[6] List, F 1841. The National System of Political Economy, trans. Sampson S. Lloyd, Green and Co., 1909.

[7] https://www.senatorbirmingham.com.au/improving-the-employment-potential-of-graduates/.

[8] McCloskey, DN. 2006. The bourgeois virtues : ethics for an age of commerce, University of Chicago Press.

[9] See Part 2.

[10] Harding et al. (2007) calls them ‘bright satanic mills’ with an obvious wink to Dickens’s ‘dark satanic mills’. See Harding, A., A. Scott, S. Laske, & C. Burtscher (2007) (Eds.) Bright satanic mills: universities, regional development and the knowledge economy. Ashgate: Aldershot.

[11] See Lock, G and Lorenz C 2007. ‘Revisiting the University Front’ Studies in Philosophy and Education 26(5): 405-418.

[12] Brown, A. 1981. ‘How the administration grows: A longitudinal study of growth in administration at four universities.’ Research in Higher Education 14(4), p. 335-352; Gornitzka A, Kyvik S and Larsen IM. 1998. The bureaucratisation of universities, Minerva, Volume 36, p. 21-47.